.

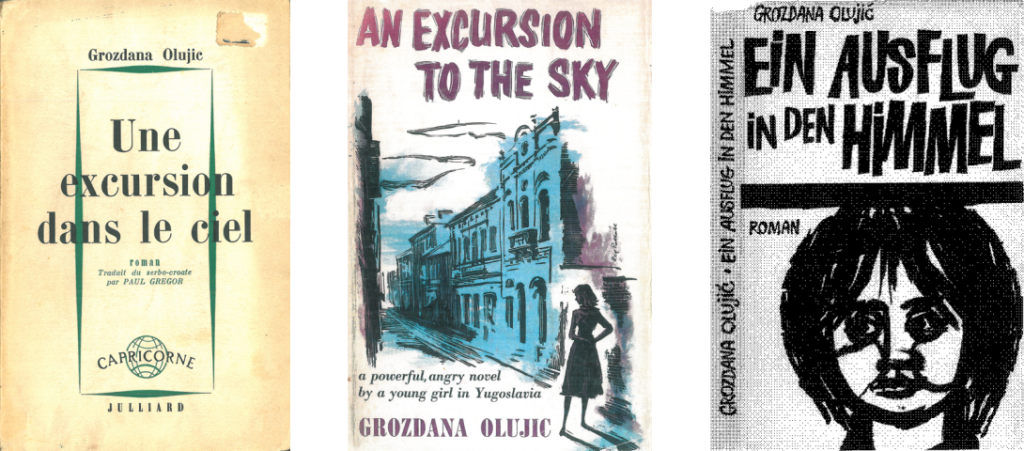

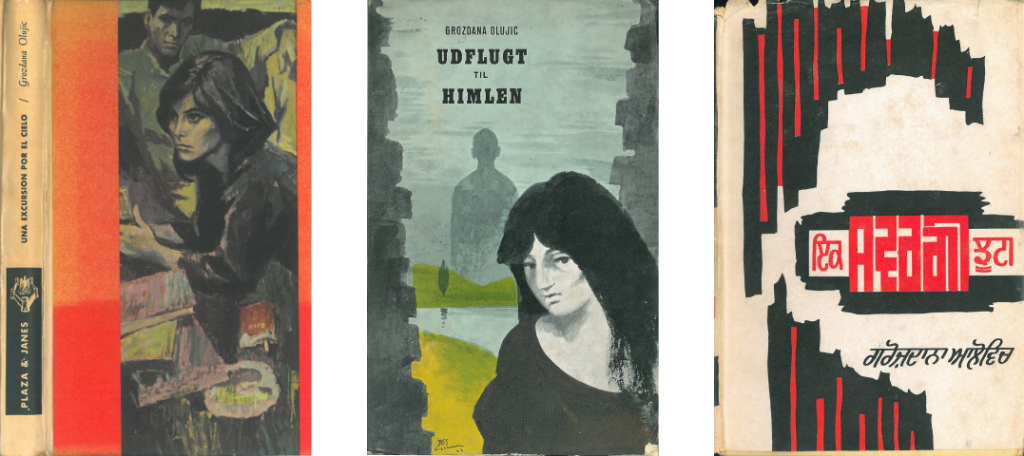

First editions

.

.

The heroes of Grozdana Olujić’s novel are young people looking for love and their own personalities. Love brings them back to their nature, unveiling all of their sensitivity and the illusion of indifference. This is a novel about a lost generation, which does not accept ideological bounds and the happiness handed by the generation which took part in the war but looks for its path for “the other side”. The other side of the novel has been criticized both by the officials and their ideological experts. The following film, “Strange Girl” (“Čudna devojka”), is the first film belonging to the so-called “black wave” of Yugoslavian cinema.

Prof. Aleksandar Jovanović.

.

The novel “An Excursion To The Skyen” by Grozdana Olujić is a book about the sufferings and the blisses of a Beatnik generation trying to find a foothold within a collapsing world… the war and its horrors are masterfully intertwined in the novel’s plot. What these young people have experienced during childhood entitled them to be “beaten”, emotionless, and demoralized more than any other peer in Great Britain or the United States of America. The book is brief, terse, surprising.

(Times Literary Supplement, London 20 April 1962.)

.

This is, in fact, a new type of romantic novel where the style’s steadfastness conceals internal tenderness… This moving love story, written with the same soul of Albert Camille’s novels, is a genuine contribution to contemporary European literacy, reflecting the despair and the indifference of the adult generation when faced with the total war’s horrors and its devastating outcomes.

(Punch, London, Аpril 1961.)

.

Footnote: the novel “An Excursion to Heaven” (“Izlet u nebo”) has been translated into English – editions in the US, Great Britain, and India, French; it has also editions in Belgian and French, as well as Dutch, German, Danish, Norwegian and Spanish; the novel “I Am Voting for Love” (“Glasam za ljubav”) has been translated into German, Russian, Ukrainian, Finnish, Dutch, Albanian, Macedonian, Bulgarian and Hungarian; the novel “Don’t Wake The Sleeping Dogs” (“Ne budi zaspale pse”) has been translated into Polish; the novel “Wild seeds” (“Divlje seme”) has been translated into English (editions in the US, Great Britain, and India), Finnish and Hungarian; the novel “Voices in the wind” (“Glasovi u vetru”) has been translated into French, Russian and Bulgarian.

.

The following films have been realized based on the texts of the novels “An Excursion To Heaven” and “I’m Voting For Love”:

“Strange Girl” (“Čudna devojka”, 1962), direction: Jovan Živanović, script: Jug Grizelj and Grozdana Olujić (Avala film).

“I Vote For Love” (“Glasam za ljubav”, 1965), direction: Toma Janić, script: Toma Janić and Grozdana Olujić (Bosnian film).

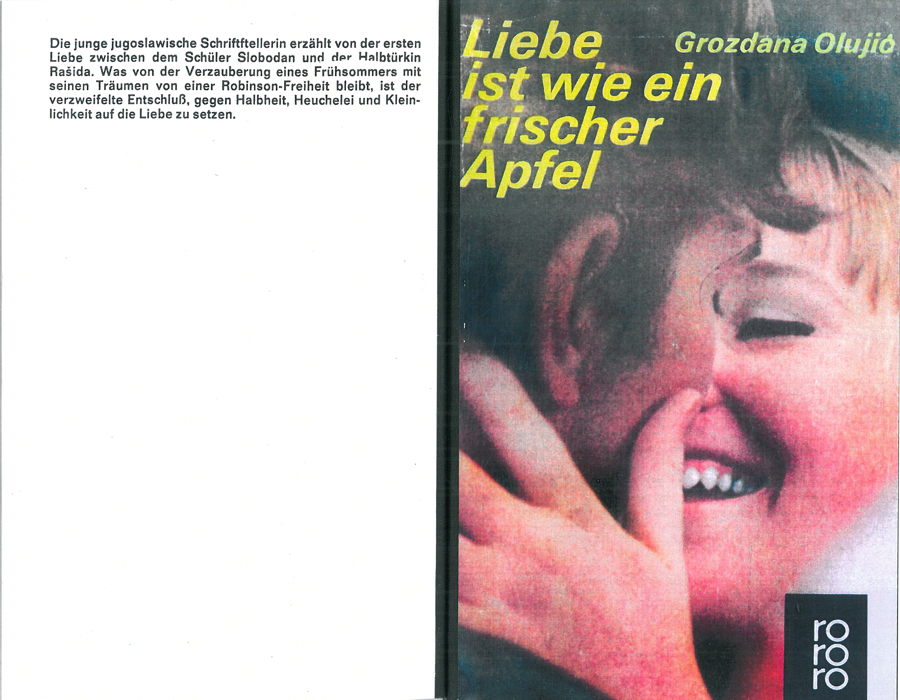

The novel “I’m voting for love” (“Glasam za ljubav”) focuses on the growth of Slobodan Galac and her girlfriend Rashida in the provincial town of Karanovo. Grozdana Olujić analyses the truthfulness of her feelings towards scholastic and familiar problems, shaping a complex frame of interpersonal relationships and unusual human destinies. This is the first “children’s novel” of former Yugoslavia, after which a namesake film has been shot; it is nowadays included in the primary schools’ reading programs.

Prof. Aleksandar Jovanović.

“International love – the first love knows no difference in Germany, Yugoslavia, and France: it is sweet, difficult, full of problems, fears, and hopes. Grozdana Olujić, a young Yugoslavian author, has written a novel about the love between a girl who, at a time, is no longer a child, but neither is a woman yet – Rashida, and Slobodan: students and dreamers experimenting during summer. There is a nice irony in her narrative on the human vices and struggles, but even more on love for people and life. Just in the most delicate passages, she manages to safeguard the narration’s pureness and measure. Her novel is an extremely powerful discovery of people and love… a positive example of Yugoslavian literacy…”

(Allgemaine Judische Wochen Zeitung, 14 April1967.)

.

.

The novel “Don’t Wake Sleeping Dogs” (“Ne budi zaspale pse”) is a novel talking about love, which has been composed starting from Romeo and Juliet, but here the theme is addressed from a modern point of view and expressed according to our sensibilities. The idea is that a person’s life, the real one, disappears when love steps out of it. This novel, which uses a newspaper’s news as a maxim, is written with an interesting attitude. As Grozdana Olujić’s precedent novels, it had a wide public of readers, as well as opposition from the authorities and the ideology of the moment.

In her last novel “Don’t Wake Sleeping Dogs” (“Ne budi zaspale pse”), Grozdana Olujić uses a real fact as a steppingstone: some years before, a boy and a girl chose to kill each other because they concluded that “Marriage is an institution without love” (“Brak je institucija u kojoj nema ljubavi”). In the mediocre newspaper article, which informed the public of the uncommon end of a common modern love story, the described tragic ending had been accepted as satisfying and truthful. In any case, Grozdana Olujić has not stuck to the truth of the starting story. She wrote a fluid love story, thus triggering the psychological threats that lead the reader to sincerely doubt the irrefutability of the accepted truth depicted by the article.

“Don’t Wake Sleeping Dogs” (“Ne budi zaspale pse”) is a novel in which Rasha, a suburban young man, comes to Belgrade to study without a scholarship, marries Milena, and meets Tisa, spending the summer being absorbed by a passionate love; after that, Tisa and he decide to commit suicide: Tisa dies and Rasha survives. Notwithstanding that, he recalls with haziness, hiding from himself and the others the truth on the last, tragic encounter between Tisa and him. This novel brings up several questions and shows the attempts to pull Rasha out of the truth he is not aware of, completing the trial which would prove his innocence. This Grozdana Olujić’s novel is a rare kind of book in our country and is indeed necessary. It concerns our own lives, where young people discover together the beauty and the pain of life, through rough contact with themselves.

(Review in Yugoslavian PEN, Spring 1965.)

.

.

The novel “Wild seeds” (“Divlje seme”) talks about a war-orphan girl looking for her own identity since her memory did not store anything. It is the story of a human being who is estranged from all possible connections and hypotheses of birth, origin, name, and religion. In the pursuit of her own identity, she meets a man who can no longer recognize the face of the world he had fought for, nor when this world took shape.

Completely devoid of self-deceit, this novel is a touching and technically excellent picture of the post-war emotional vagrancy – and still flourishing. Lika, whose real name is unknown, is left in an orphanage in Belgrade when she is about three years old. When nineteen years old, she places an advertisement asking for a certain pop family’s help. Shouldn’t them all – she wonders – be hosted what she calls a series of generational bounds? Hundreds of answers to her ad have come and they have been summarised and well checked.

The Тimes, 29 August 1974.

.

.

The novel Voices in the wind (Glasovi u vetru) shows the events going from the end of the XIX century to the whole XX century through the story of a civil Serb family. Throughout the memory of Danilo Aracki, not only the individual identity is preserved, but so it is the identity of a whole nation and its history. The family and emigrant novel melts into a familiar saga that covers the whole XX century, two wars, and the beginning of a new civil war in Yugoslavia, where the difficult but real destiny of the individuals is shown using the novel’s characters and the destinies of its heroes. The novel has won the NIN award for the best novel in 2009.

In the novel Voices in the wind (Glasovi u vetru), a phantasmagorical inspiration coming from the writing of the tales is combined with the novel’s tissue: it is a familiar chronicle, dedicated to the tectonic disturbances, the bombings, the wars, the evacuations which have hit our people during the XX century. The hero of the novel, Dr. Aracki, manages to show the importance of memory in the self-preservation of the individual and the people in general by remembering his forefathers. His goal is also met thanks to the language he uses.

.

.

.

.

The novel is recounted from the point of view of a seven-year-old child, who portrays all of the society’s layers during the occupation days: anti-fascist diversions, deserters, war prisoners, war profiteers and traffickers, mass hangings, hidden Jews, German officers, dying students. There is a symbolic scene that shows in an impressive way the cruelty and the non-sense of war, as far as the devastation that comes with it: the partisans play over the ruins “moaning” for “the Heaven that waits for us”, whilst the few survivors look horrified at the crematoria and do the body count.

The novel describes, using the first singular person, the Second World War through the eyes of a seven-year-old child, who is probably the author of the novel himself; he was that age when the war started. At the end of the war, they are significantly older than their nowadays peers. As the author says, the war has stolen their childhood. This comes along with the description of the war’s brutality, and in this scenario, even the fight-revenge can’t be legitimized by the “Heaven which awaits for us on Earth”.

Zorana Opačić

The novel has won the Bora Stanković award in 2018.

.

Repeated editions of the novels:

.

“I Vote For Love”:

- “Glasam za ljubav”. (CD audio). Belgrade: Savez slepih (Union of the blind people), 1967.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Belgrade: Nolit, 1978.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Zagreb: Mladost, 1985.

“An Excursion To Heaven”:

- “Izlet u nebo”. Volume 1. Braille. Novi Sad: “Filip Višnjić”, 1997.

- “Izlet u nebo”. Volume 2. Braille. Novi Sad : “Filip Višnjić”, 1996.

- “Izlet u nebo”. Belgrade: SKZ, 2010.

- “Izlet u nebo”. Belgrade: Serb literary association, Parthenon, 2018.

“I Vote For Love”:

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Belgrade: Bookland, 1996.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Belgrade: Bookland, 2003.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Podforica: Narodna knjiga, 2009.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Podgorica: Narodna knjiga, 2011.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Belgrade: Faculty of teacher training, 2012.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Čačak: Pčelica, 2013.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Čačak: Pčelica, 2015.

- “Glasam za ljubav”. Čačak: Pčelica, 2017.

“Voices In The Wind”:

- “Glasovi u vetru”. Serb literary association, Partenon, 2018.

“Survive Until Tomorrow”:

- “Preživeti do sutra”. Belgrade: Serb literary association, Partenon, 2018.

“Wild Seed”:

- “Divlje seme”. Serb literary association, Partenon, 2018.

“Don’t Poke Sleeping Dogs”:

- “Ne budi zaspale pse”. Serb literary association, Partenon, 2018.